Reconciliation is an ongoing process, and if we are truly committed to it, we must welcome engagement with awkward and difficult situations that must be rectified. This is one such engagement story from our campus.

Severn Cullis-Suzuki, PhD Student in Anthropology

It was exciting to return to my home city to start a PhD in Anthropology at UBC in September. Ten years ago I moved to Haida Gwaii, marrying in to the community of Skidegate. There I joined the movement to revitalize the Haida Language - with only a precious few elders left, I began to learn so that I could teach my Haida children. After several years, I started to coordinate programs and support other adults and children learning Haida as well. But I had no background or training in this work. So my plan now was to return to school to gain skills to bring back to the community to help our cause. I want to be part of the wave of 21st century academics and anthropologists working with communities for language survival and cultural empowerment.

I wasn’t expecting to find myself part of cultural appropriation of my own husband’s clan, on my very first day on campus!

The "Sea Monster"

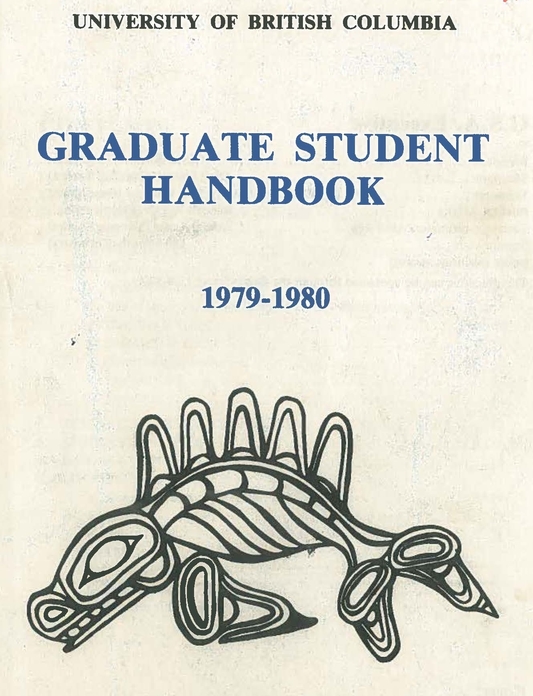

After keenly attending the graduate student orientation, I took home info sheets, as well as the sunglasses given that I received as a proud new member of the Grad Student Society. My gear-loving husband picked up the sunglasses, scrutinized them, and said, “hey, that’s our crest.” I picked up the glasses, and saw the GSS “sea monster” logo. It is actually the five-finned ‘sea monster’ crest of my husband’s Ts’aahl clan.

The Ts’aahl Eagle clan is a strong Haida clan from the west coast of Haida Gwaii. K’aagwaay, the five-finned sea monster is their most predominant crest, a supernatural being. Gyaagang.ngaay, crests are clan-specific symbols representing family ties, histories and rights and privileges; they are a significant part of the wealth belonging to any clan. You are only allowed to wear your own clans’ crests. Crests are only given through extremely cultural and political transactions. The transfer or gifting of crests outside of lineage is rare, and can only be done by those who have rights to do so at a potlatch.

What a way to start my Anthropology career! I hadn’t even attended a class and I had appropriated my own husband’s clan crest! The irony. I called the GSS office, asking if anyone knew what the logo was, or could tell me the history of the crest. I was told that it was a ‘sea monster’, and that it was given to them by a Haida artist, but that was all. Finally someone emailed me with the name of the Haida artist – Henry Young, who was credited inside the 1979-80 GSS handbook with the words: Cover: “Haida Indian Drawing of the SEAMONSTER, “Qayae I” by Henry Young”. That is all the documentation I have been presented with. Henry Young was an important Haida man in Skidegate. He passed away several decades ago, and some of his artwork, including this drawing, has been published in books about Haida Gwaii. My husband’s mother, a Ts’aahl culture holder named GwaaGanad Diane Brown, knew and worked with Henry Young.

At the GSS, the Ts’aahl five-fin sea-monster is everywhere – on sunglasses, on pins, on every card of congratulations for finishing a PhD, even etched in glass at the GSS offices. When I finally drew up the courage to tell GwaaGanad that our Grad Student Society has the Ts’aahl crest for their logo; needless to say, she was quite upset.

With no record of the transaction, there is no validity to the use of the crest by the GSS. As Indigenous Commissioner Amber Shilling tried last year to alert the Society, with no story behind the logo, it is just plain old appropriation.

In academia, using someone else’s words without citing them, and even someone else’s ideas without citation, is one of the highest academic offenses. Academic citing is similar to the accountability in oral cultures: transactions such as the gifting of rights, naming, and apologies are done publicly, with many witnesses, who are in fact paid at the end of the event to be just that, witnesses. These witnesses must remember and vouch for the transaction. The participants in the transaction must be able to cite who gave them the name or rights, when, and where.

Towards Reconciliation

I am glad to report that the GSS president, History grad student Genevieve Cruz responded swiftly and appropriately. Though she inherited this issue from three decades ago, she saw that the current admin had to take it on. Indigenous Commissioner Amber Shilling had given the GSS executive team and staff hours of training in cultural appropriation, so they understood the significance. Genevieve and the GSS council (a council made up of elected members from every department) voted to cease the use of the logo and have committed to making it right. After consulting with Ts’aahl members on what would be an appropriate protocol, they are crafting an apology which they will offer to Chief Gaahlaay, Lonnie Young of the Ts’aahl clan, along with a gift, at a public event at UBC this spring. On Ts’aahl member Judson Brown’s recommendation, the GSS will commission a local Musqueam artist to create an appropriate design that will be voted on to be used as the new GSS logo.

We are in a time of great transition in our relationships, as settlers and Indigenous peoples. For me, a non-indigenous ally and adopted clan member, moving back to the city after a decade away, it is incredible to see the progress we have made. Acknowledgements of territory are now required practice at public events; even the City of Vancouver acknowledges that it is on the unceded lands of the Musqueam, Squamish and Tsleil-Waututh peoples. That is a radical shift that is significant not only symbolically, but for our very identity as Vancouverites and as Canadian peoples – a shift from the false narrative that Canada was built on empty land, a narrative that erases indigenous people. Today’s increasingly common use of the word unceded, a legal term, is powerful in unsettling the ingrained concept of land ownership in a capitalist and Western culture, and creating a more honest understanding of history, and the ongoing occupation in which we are complicit.

I remain committed to the academic project, and the power and possibility of academic institutions as agents of change. My purpose in sharing this story of the GSS logo is not to shame anyone; my purpose is to use this as an example of the realities of our commitment to reconciliation. Reconciliation is an ongoing process, and if we are truly committed to it, we must welcome engagement with awkward and difficult situations that must be rectified.

By enrolling, we become part of the Ivory Tower, and must know and own the historical baggage of past unbalanced relations. But it also means we have every right and responsibility to change the Tower itself. I believe that today, in 2017, to be an anthropologist, you have to first commit to Reconciliation. This commitment means we will face many uncomfortable situations. But it also means that we will be able to positively contribute to strengthening language diversity, cultural resilience, and earn deep learning in our pursuit as students of knowledge and truth.